Researcher of the Month

New study links energy drinks to mental health problems in young people

We’ve all seen the vast array of colourful cans and bottles in the supermarket. Perhaps you are a fan yourself. But did you know that, in 2020, the energy drinks market was worth $45.8 billion globally? It is a large and expanding market, projected to grow at an annual rate of 8.2%, and reach a whopping $108.40 billion by 2031. Despite the fact that these products typically contain very high levels of both caffeine and sugar, and warnings on labels that they are ‘not recommended for children’, they are extremely popular with young people.

In fact, if you have offspring of a certain age, you are likely aware that 2023 was the year of Prime, a product popularised on social media. Initially, Prime was a hydration drink, but the range has since expanded to include an energy drink containing caffeine. It became so popular among teens that bottles were spotted selling for £18 in some shops (and more on resale sites), despite the recommended retail price being only £2.99.

Research from a few years ago had already found that up to a third of children in the UK consume caffeinated energy drinks on a weekly basis and ranked young people in the UK as the biggest consumers of energy drinks in Europe for their age group. 13% identified as high chronic consumers – having energy drinks four to five times a week, or more.

Published today (15th January), the most comprehensive evidence review to date has found that consuming energy drinks is associated with a wide range of risks, including increased risk of mental health issues among children and young people.

Our researcher of the month, Professor Amelia Lake, along with co-author Dr Shelina Visram and the rest of the team at FUSE (the Centre for Translational Research in Public Health) at Teesside University and Newcastle University, examined data from 57 studies of over 1.2 million children and young people from more than 21 countries. The study’s findings build on earlier research and highlight numerous risks associated with energy drinks.

Summary

What exactly are energy drinks?

A wide range of energy drinks can be found on retailers’ shelves, and there are equally wide variations in flavours, ingredient lists and caffeine content. However, it is not uncommon for a 500ml can of energy drink to contain 20 teaspoons of sugar and the same amount of caffeine as two cups of coffee. Research on the safety of caffeine has led to recommendations that children should only consume caffeine in moderation, and have no more than 3mg/kg body weight per day. As an example, a child weighing 30kg should have no more than 90mg caffeine. A small can of energy drink may contain more than this.

Commercially available energy drinks contain between 80mg – 500mg of caffeine per can (a standard can of Coca Cola has 34mg). The amount of sugar in energy drinks can be startling and even sugar-free variants contain artificial sweeteners, which have been linked to health issues such as diarrhoea. Many energy drinks also contain other stimulant ingredients, which currently have a poorly understood evidence base.

Why are they so popular?

Energy drinks are accessible and cheap. They are often promoted on gaming sites, are frequently linked to sports (especially extreme sports) and an athletic lifestyle, and they are particularly aimed at boys. In research asking young people why they drink energy drinks, taste, price, promotion, ease of access and peer influences were all identified as key factors.

What harms are they associated with?

Professor Lake and the team from Fuse have found that energy drink consumption is more common in boys than girls and that, in addition to physical health harms associated with these drinks (which include tooth decay, insulin resistance and headaches), these products are also associated with mental health harms, such as the increased risk of suicidal thoughts, psychological distress, anxiety, depression, stress and panic behaviours. The study also found drinking energy drinks to be associated with short sleep duration and poor sleep quality, poor academic performance, unhealthy dietary habits, risk-taking behaviours and substance use (including vaping).

Professor Lake is calling for action.

It’s important to note that the evidence reviewed is mostly cross-sectional (where data is collected at a single point in time), and so doesn’t prove that energy drinks are causing these negative outcomes. However, the research team advises policy makers to adopt a ‘precautionary principle’ to prevent harm to children and young people and calls for a ban on sales to children and young people under the age of 16.

A ban is not without precedent. A number of countries have attempted to regulate energy drinks, including bans on sales to under 18s in Lithuania and Latvia. The UK government ran a consultation on ending the sale of energy drinks to children in England several years ago, and also proposed this in their 2019 green paper, ‘Advancing our health: prevention in the 2020s’. Whilst 93% of respondents to the consultation supported restricting sales to under 16s, there has been no further action. In 2022, the devolved government in Wales launched its own consultation to ban the sales of energy drinks to under 16s. Many large UK supermarkets voluntarily banned the sale of energy drinks to children after a campaign fronted by Jamie Oliver, but they are still widely and easily available.

Implications

“Energy drinks are marketed to children and young people as a way to improve energy and performance, but our findings suggest that they are actually doing more harm than good. We have raised concerns about the health impacts of these drinks for the best part of a decade after finding that they were being sold to children as young as 10-years-old for as little as 25p. That is cheaper than bottled water. The evidence is clear that energy drinks are harmful to the mental and physical health of children and young people as well as their behaviour and education. We need to take action now to protect them from these risks.”

This new study adds to the growing body of evidence that energy drinks are harmful to the health of children and young people. Professor Lake and the team of researchers behind it say that it highlights the need for regulatory action to restrict the sale and marketing of energy drinks to children and young people.

Implications for parents:

Parents and carers have a significant role to play in helping their children stay safe and there is much that we can do at home to make them think twice before reaching for this apparent energy boost.

Look at ingredients together. Shining a light on sugar and caffeine content can be eye-opening. Open, clear and truthful dialogue is key.

Role model. Caffeine is ever-present, so think about your own habits. For example, do you drink a lot of coffee? How could this influence your child?

Cultivate critical thinking. Energy drinks are often promoted online on social media and gaming sites and are associated with sports sponsorship and an athletic lifestyle. Nudging children to consider the aims of this advertising and think critically about what they are being shown is a crucial skill.

Use caffeine as a talking point. Tolerance to caffeine can develop, as can dependence, so be open with your child about any issues you’ve experienced along these lines. You could even use this as a jumping off point into a wider conversation about coping strategies or even addiction.

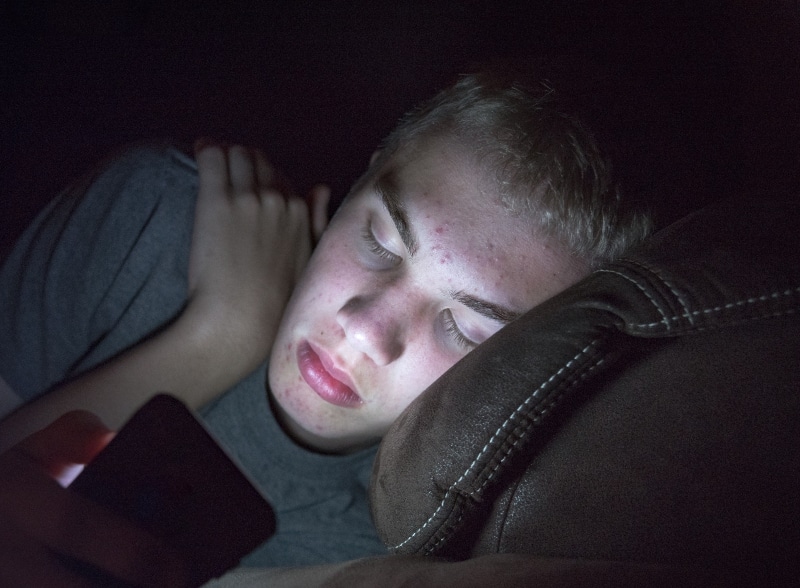

Focus on sleep. Energy drinks can be the thief of sleep, which can cause physical and psychological damage. Educate young people about good sleep hygiene. Readers in the Tooled Up community can access numerous resources which will help, including our sleep audit activity.

Be alert for accumulation and mixing. Caffeine is such a common ingredient and it is easy to inadvertently double up – for example by having an energy drink plus a caffeine-containing cold remedy – and it is a common, and potentially problematic, mixer for alcohol for many young people.

Any school or parent looking for some information to share with children should download a fact-filled leaflet which the FUSE team has co-produced with young people. Tooled Up members can check out our Quick Guide to Energy Drinks, created in partnership with drugs education charity, the DSM Foundation.

Resources Created from and Related to this Research

Professor Amelia Lake, Professor of Public Health Nutrition, Fuse, the Centre for Translational Research in Public Health, at Teesside University.

Professor Amelia Lake is a dietitian and public health nutritionist at Teesside University. Amelia is Associate Director of Fuse, The Centre for Translational Research in Public Health (http://fuse.ac.uk/) and is the Fuse lead on the NIHR School of Public Health research theme ‘Health Places, Healthy Planet’. Amelia’s research involves transdisciplinary collaborations to examine how the environment interacts with individual behaviours. Her current work is around healthy planning policy, food insecurity, energy drinks, workplace health, food systems, school food environments, the obesogenic environment and knowledge exchange. Amelia has extensive experience of working with policy makers, practitioners, non-specialist audiences as well as academics, and has produced training programmes as well as short films. Amelia also runs a small charity called The David Ashwell Foundation funding research into a rare lung diseases affecting newborn babies in memory of her son David.